Navigating Masculinity in Pakistan

How 'Zindagi Tamasha' and 'Joyland' shed a light on different aspects of Pakistani masculinity

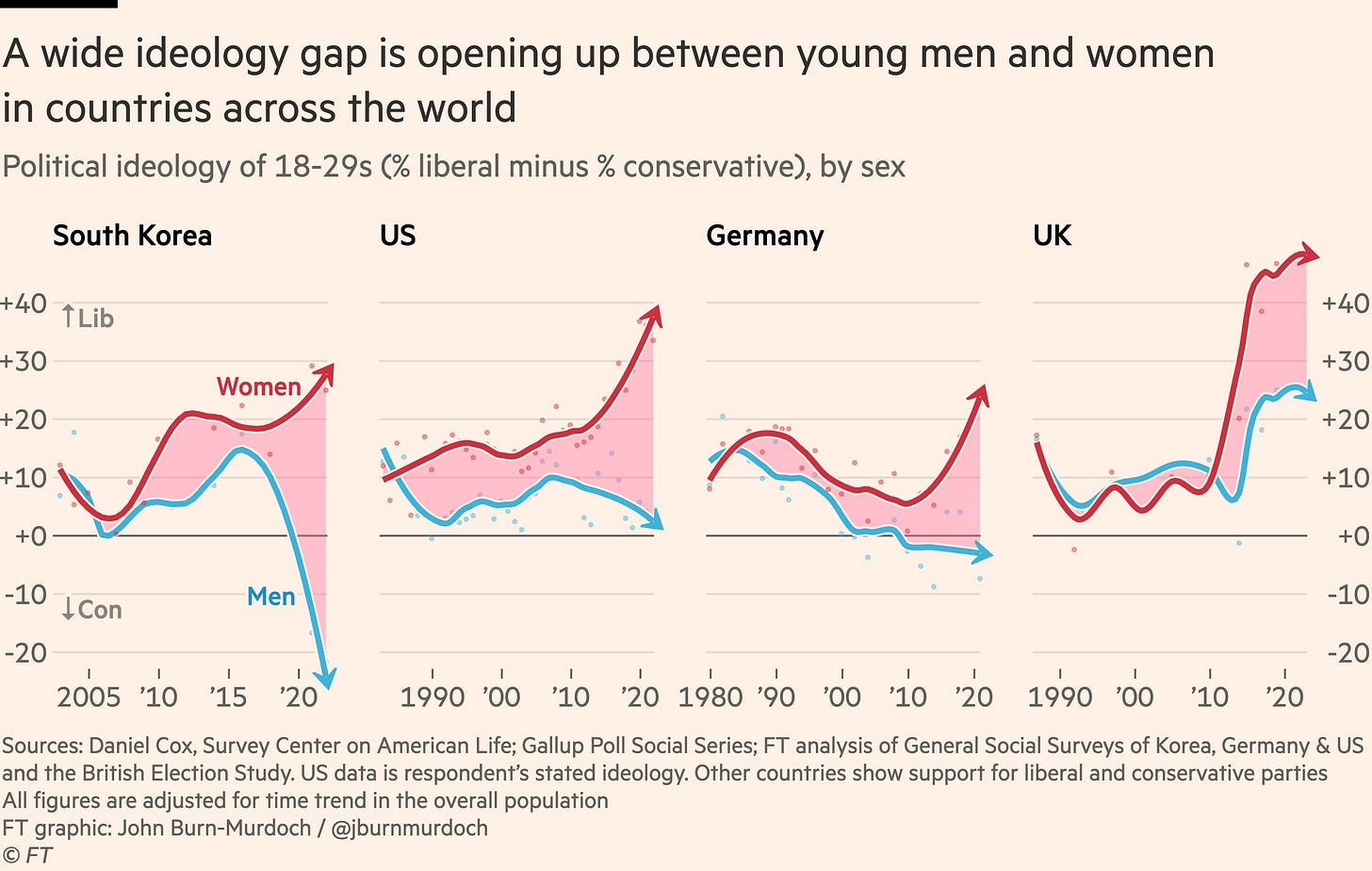

It seems like masculinity has hit a bit of a crisis worldwide. Be it the ‘loneliness epidemic’ or the ‘men’s health crisis’, men are suffering everywhere. I’ll leave a graph and a tweet here which point towards one reason this may be happening:

Pakistani men, perennially feted as breadwinners, mama’s boys, beneficiaries of arranged and cousin marriages, and considered ‘providers’, are facing the same issues (some of which are mentioned here) that their brethren elsewhere are, maybe even more. There is an ever-increasing number of women in colleges and workforce, upending the hierarchy. One coping mechanism for young men has been to move to a more incel-oriented lifestyle, worshipping people like Andrew Tate and Jordan Peterson (those two don’t see eye to eye on most issues), and even turning towards a more patriarchal version of religion. Another way is to look inwards, accept the evolving gender roles and get with the times. Two recent indie movies from Pakistan, both of which are not easily accessible in Pakistan (unfortunately), showcase how different types of masculinities in Pakistan coexist.

‘Zindagi Tamasha’ (Spectacle/Circus of life), is a film by Sarmad Khoosat, that was initially allowed to be played in Pakistani theaters but after a bit of bureaucratic ping-pong, banned from wide release. It was recently uploaded on YouTube, and can be seen here. It is the story of a lower middle class man in Lahore, Rahat, who sings religious hymns (songs of praise of the prophet), who gets caught on camera dancing to the tune of a romantic ballad at a wedding, among his friends. The video goes viral and his whole life gets upended because of it. The alienation starts with his family, where his own daughter is upset at him and doesn’t want to talk. Everywhere he goes, he is a pariah. Friends avoid him, strangers point at him. He becomes a laughingstock. To himself, he has committed no grand sin, nothing that should result in such disproportionate response. It was just a silly thing that one does among close friends. Once he realizes what has happened, his first response is to go and beat the kid who made the video. During his subsequent redemption efforts, he is asked to record an apology in presence of a molvi. The two pivotal scenes in the movie involve interaction between Rahat and that molvi. In the first one, during the apology scene, the molvi says, “there is no room for questioning”, and in a later scene, he asks Rahat, “should I ask my followers to raise THE slogan?”. By the slogan, he means a slogan to label Rahat as disrespectful to the Prophet, which would threaten his life. There is a long history of Punjabi men killing other Punjabi men over disrespect to the Prophet, the most famous being Ilm Deen killing a Hindu publisher in Lahore in 1929.

In domestic life, Rahat is not the typical Patriarch. His wife is bed bound due to illness and he does all the domestic chores (cooking, cleaning, washing clothes). His only ‘indulgence’ is watching old movies and certain songs more than others. It is this indulgence and his once slip up that costs him his friends, social circle, clients and even his daughter. Some other things that I noted watching this film included the unusual intimacy between Rahat and his wife, which is not that unusual in Pakistani couples living in Pakistan, Eman Suleman (playing Rahat’s daughter) being constantly pensive throughout the film, a “gay” gathering which is a huge stereotype of what a ‘liberal’ gathering looks like in Pakistan and Rahat’s delusion that he could re-enter society after his ‘infarction’. A small subplot involves Rahat helping Transgender** people who are a pivotal part of Pakistan’s social fabric, but mostly as objects of ridicule, occasional curiosity and frequent disgust. In the filmmaking sense, I felt as if Inner city of Lahore (Androon Lahore) is as much of a character in this film as any other actor (akin to Baltimore in ‘The Wire’). The last half-hour of the movie are droll and could’ve been trimmed down. Rahat’s betrayal of the “gay character” of Adeel Afzal at the end, adds a complexity to Rahat’s character (the persecuted person piles misery on ean even more persecuted/queer minority).

Zindagi Tamasha is a contrast between Rahat’s more modern masculinity and the society’s majoritarian hyper-religious, macho-man, masculinity in which he finds no space. He finds temporary refuge with the Transgender community but it is a small part of his life. He is left as a man without a country.

Another recent Pakistani film tackling this issue is ‘Joyland’ by Saim Sadiq, which is available on-demand on Youtube and other platforms. Joyland is a more visceral, brainy movie in some ways than Zindagi Tamasha, there is a lot more subtext in the film, and the depiction of masculinity in the character of ‘Haider’ is not a macho-man or an effeminate man, it is something Zahra Malkani referred to as ‘Reluctantly Daddy’

The film is abundant with examples of how often men choose not to help women, not to love women, not to try to make the women they claim to love’s lives just a little bit easier. Their inaction leaves women vulnerable, throws them under the bus, or just adds to the endless list of shit they have to do that day. Yes, these men suffer the patriarchy too. But any violence they may be subject to for their inability to perform perfect masculinity - whether its due to class, disability, desire - is so effortlessly displaced onto or absorbed by the women in their lives. But the curse the men are left with is the greatest curse of them all - the curse of their reluctance towards the most profound and ecstatic craft we are called upon to practice and experience in this life: Connection, care.

We see some of the many fault lines in Pakistani middle- and lower middle-class society: the burning desire to have a ‘son’ by Haider’s elder brother, elder neglect in the name of respect, the lack of space where a married couple can be intimate in a multifamily home (Manto wrote about this in lack of privacy in one of his short stories), women being forced to leave jobs and instead being asked to do household chores, Haider’s desire for his transgender ‘boss’ (Biba) but not having the guts to kiss her, Mumtaz (Haider’s wife) being neglected by her husband for days and having to rely on random strangers to fulfill her desires, Mumtaz’s resolve to get out of this rotten system by any means possible and ultimately killing herself, Biba not being given the chance to dance on stage despite the shenanigans of a female dancer, how Biba is ridiculed in her absence by her male backup dancers and then shutting them down.

Despite being weighed down by her in-laws and even her husband, Mumtaz is the clear star and conscience of this film. She lives by her rules and dies by them too.

Both of these films have an imprint of Sarmad Khoosat on them. The only previous Sarmad Khoosat film I saw was ‘Manto’ which I wasn’t a big fan of. Zindagi Tanasha and Joyland are an evolution in his style and thinking in terms of filmmaking. Joyland is slightly superior in craft and the storytelling is more nuanced than Zindagi Tamasha. But both of them are well worth your time.

**When I was growing up on the outskirts of Sialkot, a small town in northern Punjab, I had frequent interaction with transgenders/eunuchs/”Khusray”. They ran a tea shop outside my father’s clinic, above which we lived in a 3 bedroom house. I would often go and buy biscuits (Americans call them butter cookies for some odd reason) from them. During my pre-teen interactions with them, I found them to be quirky, funny, and vocal. The shop closed when I was about 7 or 8 and they moved elsewhere.

I really hate that factoid about South Korea because that abrupt drop experienced by young men was mainly caused legislative elections that took place after a presidential election where the winning candidate promised to reform mandatory military service, but never actually did. While the gender gap is still there, it's way more in line with other countries. Any decent survey of the last presidential election makes it clear that Yoon mainly won thanks to middle-aged Seoul suburbanites turning on the liberals.

I'm not attacking you or anything, obviously this wasn't your fault, and I doubt you could have found out about any of this any way aside from my taking time to tell you in the comments. I'm just irritated that this statistical anomaly is never corrected so even years later its cited as if it were an unchanging fact of South Korean politics. It's too convenient for too many people in the English language to just use sexism as a simple explanation for every bad thing that happens in South Korea instead of interrogating its actual political environment.

A good analysis on masculinity and ongoing changes in dynamics in Pakistan. Both movies are a great watch