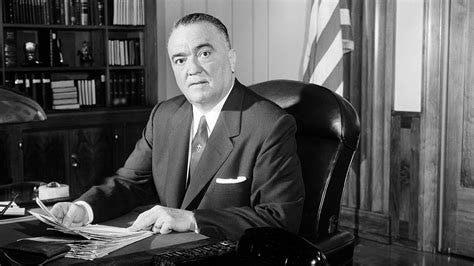

Book Review: The long, mysterious life of J.Edgar Hoover

G-man, J.Edgar Hoover and the making of the American century is a must-read

I have been fascinated by the 1960s for most of my adult life. To me, it was an era marked with huge cultural changes, both positive and negative. The baby boomer generation grew into adulthood during the time and to a certain extent, rejected the ‘old ways’. Bob Dylan’s ‘The Times They are a-changing’, released in 1964, seems to me like an anthem for the era. I’ve watched documentaries, read books, and talked to people who were alive at the time about what they felt. The Kennedy administration, with its youthful advisors and promise of a new beginning, embodied the ethos of a new generation. There was upheaval and there was a lot of violence too. Over the years, I have come to learn about the ‘other’ side of this time period, when a vast majority of people did not support the changes that were happening around them. This cultural ‘counter-revolution’ is well-documented in Rick Perlstein’s “Nixonland”.

J.Edgar Hoover was born in 1895, and dominated the American cultural and political landscape from the 1930s till his death in 1972. Beverly Gage’s magisterial work on Hoover is Robert Caro-esque in its detail and provides a masterly narrative on a pivotal public figure’s life. It is a lengthy book and took me months to finish the e-book on Kindle. By the time I finished it, the book had been awarded the Booker Prize, which it amply deserved. Hoover was a unique figure in American political history. He single-handedly molded the FBI in his image and gained so much power that even Presidents had to be careful not to upset him. His worldview was formed at George Washington University (GWU), which consisted of a strong bias against African Americans and Communists. He was part of a fraternity that sympathized with the KKK. Throughout his reign at the FBI, he was constantly finding ways to either shore up the ‘Red Scare’ or to stifle social progress/civil rights work by African American people. He was a bureaucrat through and through, obeying orders, but some more than the others. Due to fortuitous circumstances for him (WWII for instance), he was able to build a massive surveillance system that primarily spied on blacks and unions. He ramped it up with propaganda and internal disruption efforts (COINTELPRO) in the later years.

There are many surprise details in the book, at least for me. Hoover was a lifelong bachelor (code for gay back in the day) and his “assistant” accompanied him to parties and dinner and vacations everywhere, without anyone batting an eyelid. Any rumors about that arrangement were quashed by Hoover or his network of ex-FBI agents who proliferated halls of government and the private sector. Hoover spent most of his life in DC and almost never left the United States. He was extremely territorial and abhorred the people running SAS and later, the CIA. During the Joseph McCarthy witch-hunt trials, he refused to provide FBI files to congress. He would rather have people punished or caught than expose the ultra-secret stuff (like nuclear secrets or bugging foreign embassies). He was a singular character in conservative circles who hated the federal government, but were in favor of Hoover doing his job.

He resisted any changes within the FBI, despite multiple efforts. He hated Robert Kennedy, his boss for many years, mostly for his cavalier attitude while in office. He was reluctant to give away any investigative power to the Warren commission, formed to investigate JFK’s murder. He reluctantly tried to find people involved in lynchings in the South but ran up against local solidarity among white southerners. He hated Martin Luther King Jr. and would vent to any and everybody about the Reverend’s extra-marital affairs and shenanigans that were recorded by the FBI (still under seal for another 10 years, per a court order). He tolerated ‘Democrat’ presidents but thrived under Republican administrations. He was very close friends with Nixon.'

In the 1960s, he was on the wrong side of history on multiple occasions. He announced catching MLK’s killer on the day that Robert Kennedy was shot. He was not very enthusiastic about the JFK murder inquiries and obstructed their work as much as possible. He was as much an anthithesis of the ‘progressive’ 1960s as one can imagine.

There is this and a lot more in the book. For anyone interested in a history of the FBI or even a brief history of the United States in the first half of the twenty-first century, this book is a quality read.